John Ashton - Susannah Foxwell Family Group

| Parents | Parents | |||||

| Richard Foxwell |

Susannah Bonython |

|||||

| b. abt. 1604 possibly in Exeter, Devon, England | bp. Feb 1614 at St. Breage, Cornwall, England |

|||||

| d. ate 1676 in Scarborough, Maine | d. ? | |||||

| HUSBAND | WIFE | |||||

| John Ashton |

Susannah Foxwell | |||||

| b. About 1638 in England | b. About 1646 in Saco, Maine | |||||

| d. bet. 1714 and 3 Dec 1720 in Marblehead, Essex, Massachusetts | d. After 1678 before 1691 | |||||

| Relationship Events | ||||||

| Marriage | Abt. 1663 | John Ashton to a daughter (possibly Agnes) of Andrew Alger in Scarborough, York, Maine | ||||

| Marriage | Abt. 1666 | John Ashton to Susannah Foxwell Scarborough, York, Maine | ||||

| Marriage | 30 Jul 1691 | John Ashton to Mary Edgecombe Page in Marblehead, Essex, Massachusetts | ||||

| Children | ||||||

| Mary Ashton b. abt 1665 in Blue Point, Maine; m. Daniel Libby 23 Feb 1687 in York County, Maine; six children: Sarah, Daniel, Joseph, Beulah, Hephzibah, and Mary Libby; d. after 1737 in Marblehead | ||||||

| Samuel Ashton b. abt. 1666 in Blue Point, Maine; m. 15 Jul 1685 Mary Sandin in Marblehead; seven children: Ephraim, Miriam, Elizabeth, Samuel, Mary, Sarah, and Joseph Ashton; d. bef. 29 Jul 1732 in Marblehead | ||||||

| Susannah Ashton b. abt. 1667 in Blue Point. Maine; m. in Marblehead, Joseph Codner, no children; no trace | ||||||

| Elizabeth Ashton b. abt. 1668 in Blue Point, Maine; m. in 1690 Nicholas Merritt (b. abt. 1657 in Marblehead, d. Jun 1736 in Marblehead); ten children: Elizabeth, Nicholas, Mary, Samuel, Elizabeth, Mary, Nicholas, Rebecca, David, and Jean Merritt | ||||||

| Phillip Ashton m. 20 Nov 1701 Sarah Hanniford Henley in Marblehead; two children: Phillip, Jr. and William Ashton | ||||||

| Joseph Ashton b. 1678; m. 1) Mary Page 4 Aug 1700 in Marblehead; five children: Susanna, Benjamin, Mary, Joseph, and John Ashton; 2) Mary Dutch Page 25 Jan 1713 in Marblehead; four children: Abigail, Charity, Jacob, and Abigail Ashton; d. 22 Aug 1725 in Marblehead | ||||||

What We Know About This Family

Noteworthy

John and Susannah Foxwell Ashton were the grandparents of four young men kidnapped in Marblehead by pirates: Nicholas Merritt, son of their daughter, Elizabeth; Phillip Ashton, Jr., son of their son, Phillip; Joseph Libby, son of their daughter Mary; and Benjamin Ashton, son of their son, Joseph.

An Overview of Their Lives

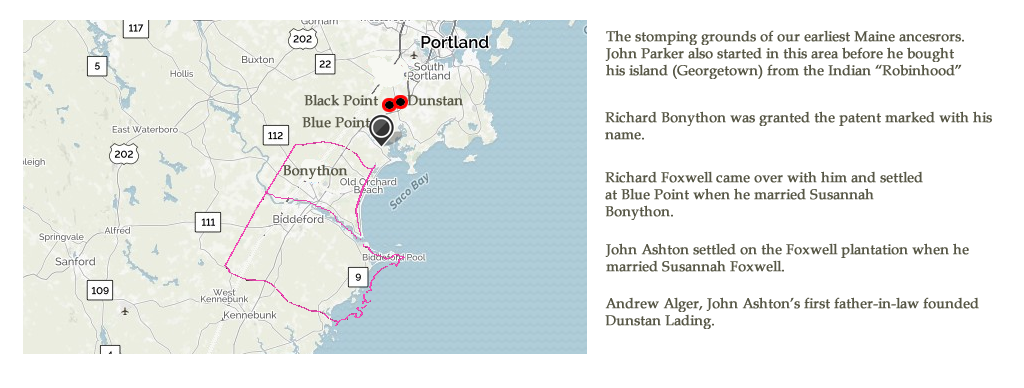

Susannah was born and raised in Blue Point in what is now part of Scarborough, Maine. Her family was very much a part of the settlement of this area, and John Ashton married into three of the founding settlers' families. Her father, Richard Foxwell, came over from England with her maternal grandfather, Captain Richard Bonython in the early 1630's.

England had granted Richard Vines with a land patent for the Biddeford side of the Saco River, and Captain Richard Bonython with Saco’s patent. Permanent settlers arrived as early as 1630. Settlements on both sides of the river were known as Saco, sometimes referred to as East Saco or West Saco. (After 1718, the entire village was known as Biddeford).

In 1631 the Council for New England granted Captain Thomas Cammock the Patent of Black Point, 1500 acres from the Spurwink to the Black Point River, back one mile from the sea and including Stratton's Islands. Cammock arrived in 1633 from Piscataqua, where he'd been the agent of Mason and Gorges. He claimed all rights to fishing and "fowling" and apportioned land to tenants from whom he collected fees and rents. Susannah's father quarreled in court with Cammock over fishing and hunting rights.

The second settlement was begun in 1636 when Richard Foxwell built his homestead close to the Dunstan River, and was joined by a neighbor soon after. The country between the Saco and the Spurwink rivers was originally called Black Point. The spruce trees covering the eastern shore of the Nonesuch River appeared black to ships, and the hardwood on the western shores of the Nonesuch and Dunstan Rivers appeared blue, and thus were the areas named. Another neighbor was Nicholas Edgecomb.

The third principal settlement of the old Scarborough was Dunstan in 1651. Andrew and Arthur Alger purchased more than one thousand acres from Uphannum, daughter of Wackwarreska, Sagamore of Owascoag County. Owascoag was the Indian name for Scarborough, meaning place of much grass.

I've been able to discover very little else about John Ashton. I know from the entry in the Genealogical Dictionary of Maine and New Hampshire that unlike many Colonial settlers, he was never deposed, nor did he hold any government positions or serve on a jury. Johanna Punchin, his sister-in-law (sister of his third wife, Mary Edgecomb) deposed after he was dead that he never owned land. No probate material has been found. His primary distinction is having married into three of the founding families in this area of Maine.

He lived at Dunstan the short time he was married to Andrew Alger's daughter, who died without children not long after their marriage. We know the names of the five other Alger children because they were named in Alger's will after he was killed by Indians, but since his daughter pre-deceased him, her first name was lost to history. John Ashton lived on the land of Richard Foxwell after he married Richard's daughter, Susannah, his second wife, and she was the mother of all his children.

By the 1650s, the small settler society between the Piscataqua and the Kennebec was beginning to develop a distinctive culture, more diverse, more secular, and more democratic than the Puritan Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bay to the south. Coastal settlers exported, in addition to fish, furs, and produce, a variety of products like clapboards, pipe-staves, ship timbers, planks, pitch, and turpentine. Their markets were other colonies, the West Indies, and Europe. Small shipyards appeared in the coves, and water-powered mills on the rivers. Farmers took advantage of coastal salt marshes to expand their herds, and they worked in seasonal trades like fishing, lumbering, milling, seafaring, and trapping. Women stayed closer to home in the kitchen, garden, barnyard, orchard, and milk-house. Some specialized in producing yarn, fabric, dairy products, or crafts, which they traded with neighbors. Which of these activities applied to John and Susannah Ashton cannot be known. nor how he supported the family while in refuge from the Indians or later in Marblehead. I can find no evidence of a probate on his estate.

During the Indian Wars, the family fled to either Grand Island in Piscataqua (according to his sister-in-law) or to Newcastle (according to the Genealogical Dictionary which says he was there in 1676). At least one and maybe three of their children may have been born while they were refugees, and Susannah died there. Their last child was born in 1678, so Susannah's death was sometime after that. John and his children then moved to Marblehead. He married 30 Jul 1691 Mary Edgecomb Page, the widow of a Scarborough neighbor, George Page. George and Mary Edgecomb may have been the parents of Mary Page who married John's son, Joseph Ashton, and Nicholas Page, who married first Mary Dutch, who then was the second wife of Joseph Ashton.

About the Children

- Mary Ashton married Daniel Libby of Maine, and the couple removed to Marblehead "with her family" in 1690. Daniel was a carter. In 1693, they moved into the home of Colonel Nathaniel Norden, who was the first aristocrat in Marblehead to own a coat of arms. They lived there for 18 years. The house was built between 1657 and 1686 and is still standing today. A photo appears in the Documents section. It became a point of interest in 2012 when a secret stairway was discovered. Colonel Norden did not have children. The entrance to this hidden staircase is beside the front door. I wonder if the Libbys used it? Daniel and Mary Ashton Libby had six children including a set of twin girls. Tragically, their son Joseph was taken into custody from aboard a pirate ship. He had been captured at the docks in Nova Scotia along with his cousins, Nicholas Merritt, Benjamin Ashton, and Phillip Ashton. Benjamin escaped almost immediately. Nicholas and Phillip were in dangerous and hard-living conditions on separate ships and exotic lands for periods of one to over two years. Joseph had been witnessed firing guns and plundering ships and in spite of his protests of innocence was hanged along with 25 others in Newport, Rhode Island in 1723. Daniel and Mary's other five children all married in Marblehead. A record shows that Daniel and Mary Libby with a grandchild were warned away from Beverly in 1731, but no reason appears in the record. Could this have been because they were the parents of a pirate? There are records of visits to their Norton relations in Manchester. Mary's mother's sister, Mary Foxwell, married George Norton. The Libbys were back in Marblehead in 1735, she still living there in 1737.

- Susannah Ashton and her husband Joseph Codner left no records whatsoever and were noted as d.s.p. Decessit sine prole (Died without offspring). John Codner of Marblehead was another direct ancestor, but I cannot find that he was a relation to Joseph.

- Samuel was married to Mary Sandin, related on both sides to our direct ancestors William Bassett and Arthur Sandin. He deeded property at Blue Point to Captain John Stacey (a descendant of another of our direct ancestors)in a document that tells us he was the eldest son of John and Susannah Foxwell Ashton and the grandson of Richard Foxwell, all deceased. (3 December 1720, dated 25 April 1721; York Co. deeds V 10 P 259, 60). He also identified himself as a fisherman. He and Mary had seven children.

- Elizabeth Ashton, our direct ancestor, married Nicolas Merritt, Jr. the son of Nicholas Sr. and Mary Sandin, both of the earliest and established Marblehead families. They had ten children. Although no death records could be found for the first three, we assume they died as infants or very young children because children with the same names arrived later. Their son, Nicholas, was among the group kidnapped on 15 Jun 1722 by pirate Ed Lowe along with his cousins, Joseph Libby and Phillip Ashton. He was one of a group released off of North Africa a few months later. Nicholas seized a ship just captured intending to set off for England, but a shortage of supplies took them to the Azores where they were arrested and thrown in jail. Nicholas remained four months in a dank cell fed on one meal of thin cabbage soup a day. He contracted a mild case of smallpox which weakened him further. He was released penniless with no explanation. He could neither speak nor understand the language, but managed to find odd jobs on the docks until a ship from New England offered him a job as a deck hand and passage home. He arrived home 20 Sep 1723 to the great happiness of his family but also to the news that his cousin Phillip Ashton was still missing and that their cousin Joseph Libby had been hanged a little over a month earlier on 19 Jul 1723. Nicholas and Elizabeth have their own family group page.

- Phillip Ashton and his wife Sarah Hanniford (Hanover) were the parents of two sons, Phillip, Jr. and William Ashton. Sarah had four children with her first husband, Joseph Henley, who died in 1699. In 1709, Sarah's father died and left the house Sarah and her family were living in to her sister, Miriam. The "Philip Ashton House" built about 1715 stood long enough in Marblehead to be photographed. That photo appears in the Documents section. Their son Phillip, Jr. was a very religious young man and resisted the commands to join the pirate activities even with the violence he met at the hands of the pirate, Ed Lowe who captured him and three of his cousins. From the website of a "cousin" who is also a 8th great granddaughter of John and Susannah Foxwell Ashton:

Philip was born on August 12, 1702 and baptized in the First Congregational Church in Marblehead, MA on April 18, 1703. He became a cod fisherman at a young age, as many boys in Marblehead did. His great adventure began in 1722 at the age of 19 when he was Captain of the Schooner Milton. Much of what we know about Philip came from the narrative he dictated to Rev. John Bernard upon his return home. This is how his adventure started:

“Upon, Friday, June 15th 1722, After I had been out for some time in the Schooner Milton upon the fishing grounds off Cape Sable Shoar, among others, I came to sail in Company with Nicholas Merritt in a Shallop and stood in for Port Rossaway, designing to harbour there til the Sabbath was over, where we arrived at Four of the Clock in the Afternoon.” They had been at anchor off Shelbourne, Nova Scotia for several hours when their vessel was boarded by pirates. Philip was carried upon the pirate ship, and he was met by the famous pirate Ned Lowe. For the next week he remained in the hold of the vessel, being brought out several times to have a pistol pointed to his head wanting him to sign the ship’s articles and become one of Ned Low’s pirates. He refused to do so. His first chance to escape came just before the vessel was to set sail. The pirates had gone ashore at Port Rossaway to get water and left a dog belonging to them behind. Two men jumped in the boat to get the dog as Philip was about to jump overboard. He was captured again, had the pistol to his head and fired, but it misfired three times, the fourth time if fired but into the water not at Philip. Philip’s journey on the pirate ship which Lowe now called “Fancy” took him to Newfoundland, to the Azores, Canary Islands and ending up near Roatan Harbor in the Caribbean.

It was here on March 8, 1723, 9 months into his journey that Philip had another chance to escape. He convinced the cooper who was going ashore to take him along, as this was an island and there was no way he could go anyplace. “I went into the boat with only an Onasburg frock and trousers on and a Mill’d cap upon my head, having neither shirt, shoes nor stockings nor anything else about me; whereas, had I been aware of such an opportunity I could have prepared myself something better.” Once ashore Ashton helped fill the casks and take them to the boat and then nonchalantly began to stroll towards the woods. Once he lost sight of the cooper “I betook myself to my Heels and ran as fast as the thickness of the Bushes and my naked feet would allow me.” So here Philip remained, having no way to make fire or prepare food, no shelter and no clothing. He did have plenty of water, fruit trees and tortoise eggs on the island. There were plenty of coconuts but he had no utensils to open them with. He built shelter by taking branches that had fallen from trees and stuck them into the ground, split the palmetto leaves and covered the branches. Unfortunately Philip was a poor swimmer and therefore could not swim from one island to the next to see what else may be available to him. The other problem was that his feet took a beating walking on the hot sand and thick brush with nothing to protect his feet.

Philip remained alone and ailing on the island for nine months when sometime in November 1723 he spotted a canoe coming towards him with an elderly Scotsman in it who had fled the Spaniards. The man remained for several days until one day he went out to hunt some wild hogs and a gust a wind came up and the Scotsman never returned. He had left Philip with some pork, a knife, a bottle of powder, tobacco, tongs and flint so now Philip could make a fire and cut up some of the tortoise for food. He now began to gain some strength. About two months later while roaming the island he found a canoe but he didn’t recognize it as the Scotsman’s. Now he had some transportation to visit some of the other islands. Around June 1724, now two years since he had left Marblehead he took his canoe to a small island, leaving his fire burning on Roatan. He spied two large canoes following the smoke towards his island so he headed back and although being scared introduced himself to the visitors. These men remained for six or seven months with Philip and nursed him back to health.

It was several months later that Philip and his friends set out for Bonacco to gather food. While there a boat came ashore to gather water and Philip noticed they were Englishman and made friends with them. They were part of a fleet heading to Jamaica for trade and one of the Brigantines was from Salem, MA. The commander was Capt. Dove who Philip knew and asked him for a passage home which Dove did and paid him for his work. It was the end of March 1725 that they set sail for Jamaica and the first of April they went through the Gulf of Florida heading to Salem Harbor where they arrived Saturday evening, the first of May 1725. “Two years, ten months and fifteen days, after I was first taken by the Pirate Lowe and two years and near two months after I had made my escape from him upon Roatan Island. I went the same evening to my father’s house, where I was received, as one coming to them from the dead, with all imaginable surprise of joy.”

He became known as the "Robinson Crusoe of Marblehead." A year after his return, on December 10, 1727 he married Jane Gallison. She died 10 Dec 1727 seven days after the baptism of their daughter, Sarah. Following Jane's death, he married Sarah Bartlett (daughter of William Bartlett and Sarah Purchase) on July 5, 1729. Together they had 6 children. His estate was probated 5 Aug 1746.

- Joseph Ashton married first in Marblehead Mary Page, possibly the daughter of George and Mary Edgecomb Page. They had five children before she died. One of those children, Benjamin, was kidnapped along with his three cousins. He escaped the same night when Lowe sent him to retrieve his dog. He took advantage of the opportunity to escape into the woods. His escape so angered Lowe that he fired three times at Philip Ashton, who survived only because the musket misfired three times. After the death of his first wife, Joseph Ashton married Mary Dutch Page, the widow of his first wife's brother, Christopher. They had four children together, and then he died when at least three were minors.

Proof of Relationship

The entry in the Genealogical and Historical Biography of Maine and New Hampshire is our best proof of relationship.What Else We Need to Learn

The goal of this project is to trace every line of ancestry to the arrival of its first immigrant to America. The basic information of each couple is considered complete when we know the dates of birth, marriage, and death for both spouses. their parents' names (or whether they were the immigrant), and the child or children in our ancestry line.

The research on this family is complete. Rechecks of available data later may fasten down some of the dates.